About Brian DeChesare

Brian DeChesare is the Founder of Mergers & Inquisitions and Breaking Into Wall Street. In his spare time, he enjoys lifting weights, running, traveling, obsessively watching TV shows, and defeating Sauron.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn what a deal done on a cash-free debt-free basis means, how it works in the context of a leveraged buyout, and how LBO models that use this deal structure differ from ones that use a standard structure.

The Cash-Free Debt-Free Basis in M&A Deals and Leveraged Buyouts: What It Means and How to Model It

Cash-Free Debt-Free Basis Definition: In a cash-free debt-free deal, the Seller’s existing Cash and Debt both go to $0 when the deal closes and are immediately replaced by new Debt and Cash balances; the new Cash is typically the company’s Minimum Cash required for operations, and the deal price is based on Purchase Enterprise Value.

The most confusing point about cash-free debt-free deals is that the name is deceptive:

But this representation misses the next step, when the target company’s Cash and Debt balances are brought up to higher levels:

Deals done on a cash-free debt-free basis are most common for private companies that get acquired by buyers such as private equity firms and large, public companies.

The short, simple explanation for these deals is the following:

Target’s Existing Cash and Debt: The Target uses all its Cash to repay its existing Debt. If there is still Cash left over, it is distributed to the shareholders, reducing the company’s Equity Purchase Price in the deal.

On the other hand, if some Debt remains after the Target has used all its Cash to repay as much Debt as possible (i.e., Debt > Cash), then the remaining Debt repayment is deducted from the proceeds that go to the shareholders.

If you think about it, this means that the shareholders effectively receive the Equity Purchase Price – as they should – because Enterprise Value – Debt + Cash = Equity Value.

Sources & Uses Schedule: The Uses side of this schedule is based on Purchase Enterprise Value rather than Purchase Equity Value and includes the normal transaction and financing fees and a Minimum Cash that the Target must maintain to continue operating.

Balance Sheet Adjustments: The Target’s Cash is brought to $0 and then replaced with the Minimum Cash, so that the post-deal balance is the Minimum Cash. The Target’s Debt is brought to $0 and almost always replaced with a new balance that is the same (in most M&A deals) or higher (in most leveraged buyouts).

Suppose that you’re considering a leveraged buyout of a private company with $50 million in EBITDA.

You plan to pay a 12x EBITDA multiple for it, which means the Purchase Enterprise Value is $600 million. The company also has $50 million in Cash and $100 million in Debt before the deal closes.

You plan to use 5x EBITDA for the Debt funding, which means there will be $250 million in Debt after the deal closes.

Here’s the cash-free debt-free version of the Sources & Uses Schedule:

The Investor Equity line is “the plug”: it equals the Total Uses of $623 million minus the New Debt Issued of $250 million.

If this were a public company instead:

1) The Uses side would be based on Purchase Equity Value, not Purchase Enterprise Value, because most public companies are acquired based on a share-price premium.

2) Assume/Replace Existing Debt would be shown on both the Uses and Sources side, and we would likely split the Debt on the Sources side into this “Existing Debt” vs. “Brand-New Debt.”

3) The Minimum Cash would not appear on the Uses side. Instead, the Target’s Excess Cash would appear as a line item on the Sources side, which is equivalent (see the last section of this article for a demonstration).

Although this schedule “looks different,” it’s equivalent to the one above because the PE firm still contributes $373 million in equity to buy this company.

Also, the Total Debt after the deal closes is still the same, at $250 million, and the company will still have $10 million in Cash – its Minimum Cash – on the Balance Sheet.

Since the Investor Equity and post-deal Total Debt and Cash are the same, we can say that these deals are equivalent, even though one is done on a cash-free debt-free basis and the other is not labeled that way.

To extend this example above, let’s now consider a full 3-statement model for a leveraged buyout.

The company in this LBO has these parameters:

Once again, the Sources & Uses Schedules produce equivalent results for the Investor Equity and post-deal Cash and Debt, assuming that the company’s existing Debt balance is refinanced (repaid and replaced) in the deal:

There is only one real difference here: in the non-cash-free debt-free version, the Target’s Debt might be “assumed,” which means it is kept in place on the Balance Sheet.

Although this happens very rarely because Debt is usually repaid in a change-of-control scenario, it is a possibility.

If this existing Debt of $50 million is assumed, then we’d either have to reduce the Term Loans and Subordinated Notes by $50 million total, or we could potentially leave them in place and assume a higher Debt balance of $248.3 million after the deal closes.

If we actually assume this higher Debt balance, the Investor Equity and model output such as the IRR will change – but it’s not because of the deal type.

Instead, they change because we used more Debt and less Equity to fund the deal.

Here’s a summary of the Balance Sheet adjustments for Cash and Debt in this deal:

And the Liabilities & Equity side looks like this:

Nothing about the Common Shareholders’ Equity calculation changes. It’s always written down 100% regardless of the deal type, the legal/advisory fees are deducted, and it’s replaced with the new Investor Equity used to fund the deal (the $426.7 million above).

You should also modify the Debt Schedule and the Returns Calculations so that they use the correct Debt and Investor Equity numbers, just in case they happen to differ under these different deal structures.

Once again, though, the main, realistic difference is that the company’s existing Debt might be assumed in the non-cash-free debt-free case, while it will always be refinanced and go to $0 in the CF/DF case, so you have to handle that in the Debt Schedule:

The bottom line is that metrics like the IRR and multiple of invested capital are exactly the same regardless of the deal structure here.

The only thing that makes a difference is the total amount of Debt used, which is why the bit about assuming the existing Debt matters the most.

However, even if the existing Debt is assumed, in a more robust model, it still wouldn’t make a difference because we’d simply scale down the Term Loans and Subordinated Notes used to fund the deal.

Mergers and acquisitions – deals where one normal company buys another normal company – can also be done on a cash-free debt-free basis.

The idea is very similar, but the Sources side in such deals differs because a normal company can also issue Stock to do deals, while PE firms never do this.

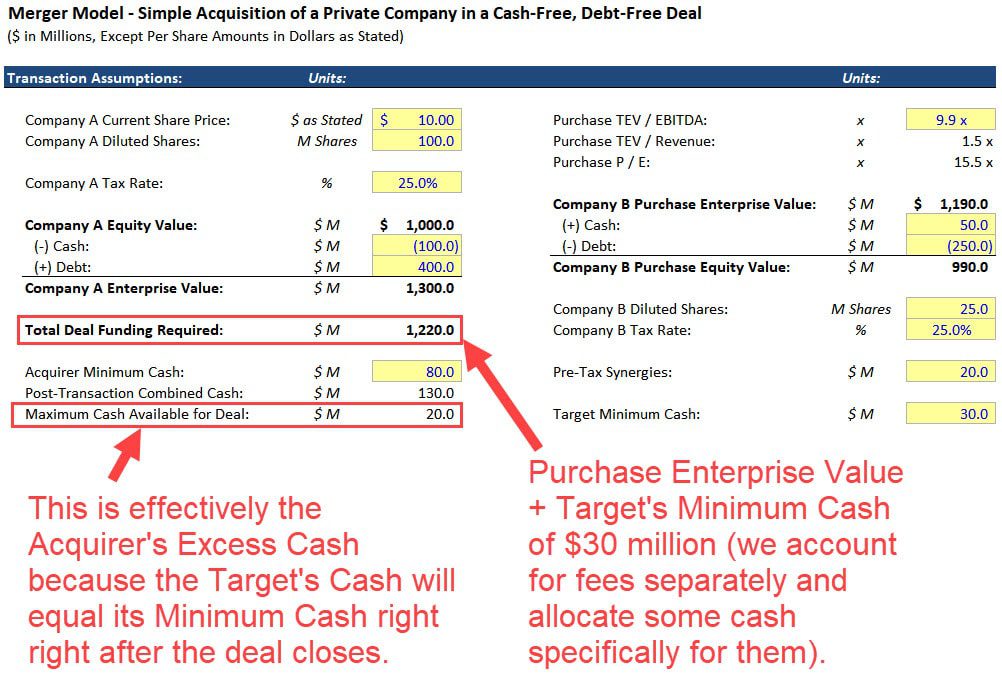

Another difference is that both the Acquirer and the Target have their own Minimum Cash balances, so you must factor in both when calculating the deal funding.

Here’s a simple example of how it affects things:

We then calculate the Debt and Stock Issued based on the Deal Funding above, the Cash Used ($20 million), and the maximum Combined Debt / EBITDA, which is 3x here.

The Sources & Uses Schedule follows the same outline as in the private LBO deals above, with Purchase Enterprise Value, Fees, and Minimum Cash on the Uses side and the deal funding on the Sources side:

The main difference here is that the “Cash Used” in an M&A deal is a bit murkier than in a leveraged buyout because the two companies combine their Cash balances after the deal closes.

Because of this issue, in most models for real/complex deals, we set a Combined Minimum Cash Balance for the post-transaction entity to avoid thinking about whether the Cash will come from the Acquirer or Target.

The key point is that the Target’s shareholders effectively get the Purchase Enterprise Value + Cash – Debt, or the Purchase Equity Value, for their proceeds in the deal.

The Acquirer might pay the Purchase Enterprise Value, but the proceeds to the shareholders are more like the Purchase Equity Value due to the Cash distribution and the need to repay existing Debt.

If you still have doubts about whether cash-free debt-free deals are equivalent to non-CF/DF ones, you can use some algebra to answer this question.

You can always rewrite Purchase Enterprise Value as Purchase Equity Value – Cash + Debt, and you can then rewrite the Cash and Minimum Cash terms as “Excess Cash” on the Uses side.

Here’s the step-by-step process to turn one Sources & Uses Schedule into another:

We can then rewrite the Target Cash and Minimum Cash terms as “Target’s Excess Cash” instead:

And then, just like in algebra, we can add the Excess Cash term on both sides to make it “cancel out” on the Uses side and appear as a positive on the Sources side:

The short answer is “possibly, but true exceptions are quite unlikely.”

For example, if the Target keeps all its Cash and does not distribute anything to its shareholders, you might think that changes the deal parameters.

But it doesn’t: the Target’s Equity Purchase Price will be higher, and the Acquirer will “get” the Target’s Cash. The Acquirer pays the same effective price because it pays more for the Target’s equity but also gets more Cash after the deal closes.

The main exception is that if the Acquirer repays the Target’s entire Debt balance without replacing it with new Debt, the deal would require additional funding and would look quite different.

But that’s not due to the cash-free debt-free basis: that’s a simple choice of what to do with the Target’s capital structure after the deal closes.

In other words, this same variation could occur with either a cash-free debt-free deal or a non-cash-free debt-free deal.

The bottom line is that while cash-free debt-free deals use slightly different assumptions, they are almost always economically equivalent to non-CF/DF ones.

Brian DeChesare is the Founder of Mergers & Inquisitions and Breaking Into Wall Street. In his spare time, he enjoys lifting weights, running, traveling, obsessively watching TV shows, and defeating Sauron.